Things Started Falling Apart

Marta “Elena” Cortez-Neavel

Content Warning: Includes mentions of intimate partner violence

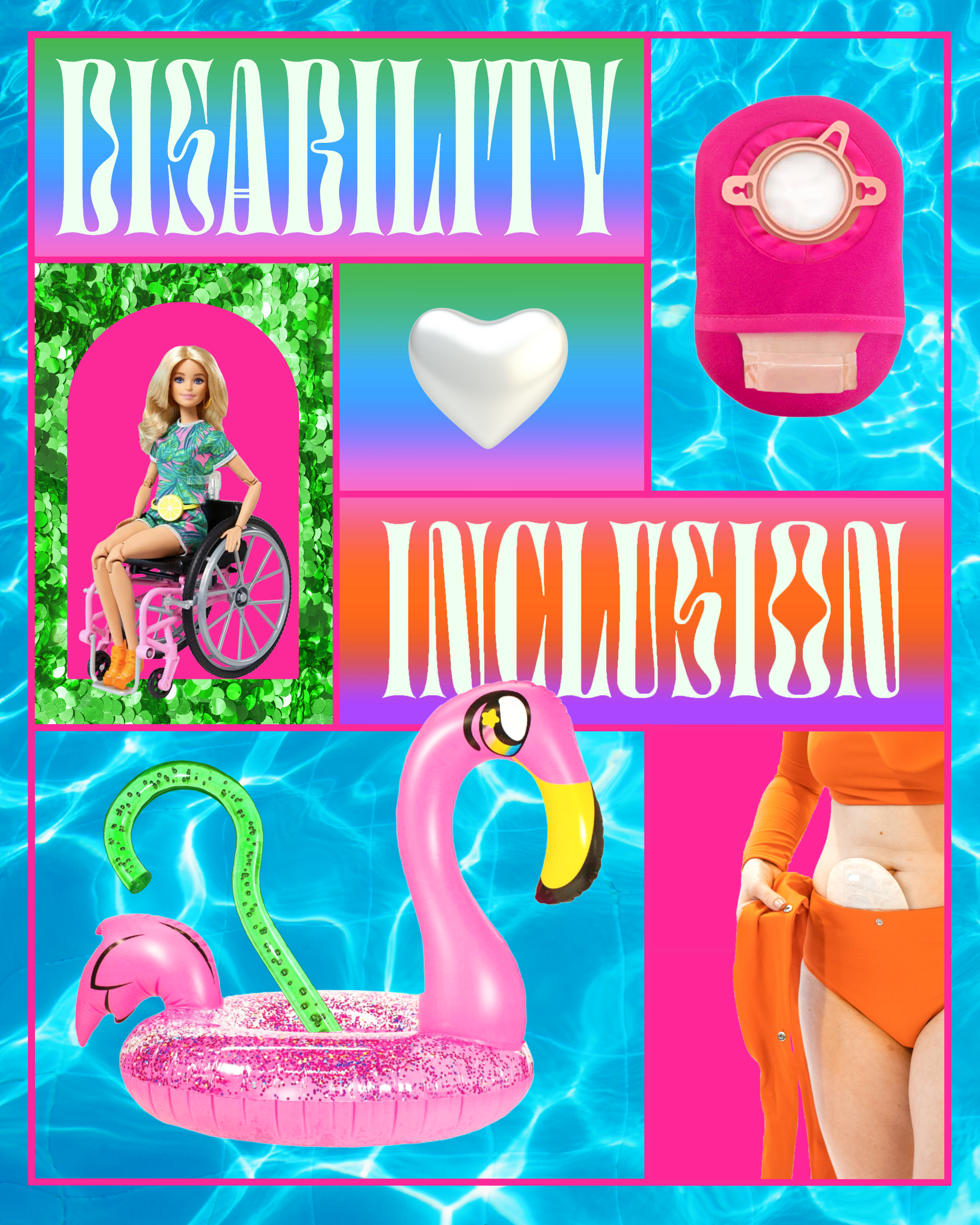

Adaptive products featured include Hot Pink “Ostomy Cover” by Abilitee, “Lydia Bikini” by MIGA Swimwear, and “Emerald City Bubble Stick” by NeoWalk Sticks

Image Description: A collage of colorful adaptive products in front of a blue pool-water background. The words “Disability Inclusion” are shown in a squiggly white all-caps font, and are staggered across the image in-between products. A rainbow gradient is set behind the words, to make them pop. Clockwise from the top: the hot pink ostomy cover is a small water-resistant pouch that fits around a colostomy bag. The pouch has a hole towards the top, and a flap at the bottom, with a beige ostomy bag peeking out. The swimsuit is shown on a light-skinned model, who is wearing an ostomy bag that is peeking out of the swimsuit bottoms. The swimsuit is an orange two-piece. The top has a high neck and long sleeves, and the bottom is a bikini brief style with a snap-on sash that can be used to cover the waist. Next to the model is a large pink flamingo inner-tube floatie, with the flamingo’s neck and head coming out of the right side of the tube, and the tail coming out of the left side. In the middle of the floatie is a bright green transparent walking cane. Above the flamingo is a blonde Barbie wearing a tropical outfit and sitting in a manual wheelchair.

I graduated from college in 2014, with academic awards, artistic recognition, a handsome boyfriend, and a small business designing adaptive clothing and accessories for pediatric patients with medical devices. Over the next few years, my business, Abilitee, grew in size and popularity, and I was accepted into half a dozen U.S. medical schools. Everything I thought I wanted for myself was coming to fruition. My life looked fantastic. But it didn’t feel right.

Not wanting to give up my newfound passion for designing adaptive clothing just yet, I put off medical school for a year. Then another year. When I finally started school in California, it didn’t go well. I was anxious, severely depressed, and couldn’t get my mind off my creative work. Instead of studying, I was researching medically-safe materials, talking to parent support groups for medically complex kids, and sewing adaptive prototypes for families to test out. This work brought me enough joy to get me out of bed in the morning, but every time I got to campus for class, I felt like I was in prison: totally understimulated, in a bleak, sterile environment, and wearing an uncomfortable “business professional” uniform.

During this time, I also became more and more involved in the growing online disability community. I had formed friendships across the world with other neurodivergent and disabled activists, and I began to hear more and more about the near-universal experience of medical gaslighting and other medical trauma, including PTSD. I collected stories of physicians and the healthcare system repeatedly, and almost predictably, failing their most vulnerable patients. I have friends who’ve been thrown around from specialist to specialist with no physical improvement, friends who have been fired by their doctors for “being too complicated,” friends who have been denied care because they are fat. But when I inquired about what physicians are doing to address these significant issues, I found nothing. When I brought up the phrase “medical gaslighting” to my physician parents, they had never heard it before. When I looked at online medical journals to see who was researching these issues, there was next to nothing. I thought, “Why is no one listening? Why doesn’t the medical community care?”

I was angry and disheartened, and became increasingly disenchanted with pursuing a career in such a fucked-up system. I felt like the work I was doing through Abilitee was making a difference. It felt meaningful, impactful, and much-needed. I heard how the g-tube pads I designed were reducing the incidence of accidental tube pull-outs in babies, which prevented excessive hospital readmissions. I heard of someone’s grandpa, who smiled for the first time since his colostomy surgery, after being gifted one of our “OH SHIT”-emblazoned Ostomy Covers. And after our Insulin Pump Belts were released on aerie.com, as part of their first ever collaboration with an adaptive accessories brand, I read social media comments from Type 1 Diabetics around the world stating things like “This changes everything! I never thought I would feel so seen and supported by such a big mainstream fashion brand.” By then, I knew this was what I wanted to do with my life, at least for the next few years. So, I dropped out of medical school.

And then COVID-19 struck the world, and my life, like an asteroid. At work, we took extreme precautions, requiring our 8-person team to work from home, or visit the office in staggered shifts, for work like sewing or packing and shipping orders. We required masks in-office, and allowed only one or two people to be there at a time. Every time someone came and left, we asked that they sanitize all surfaces they touched in the common areas. Our team switched to meeting over zoom and by phone. It was an incredibly tough year. I was co-managing a team remotely, while working on my own projects for upwards of 80 hours per week. Years into the business, I still wasn’t taking a salary. I just wanted to get the work done, and wanted to make sure our team stayed employed. I became increasingly anxious and isolated. My usual routine and support systems began to fall apart, which exacerbated the chaos and upheaval, as it did for many autistic, neurodivergent, and disabled people. I was talking with friends and family less and less. My boyfriend, who worked remotely as an attorney, started visiting more frequently, staying with me for weeks at a time. Just us two and my dog, Archie, almost completely isolated from the outside world. That year is when the fighting, gaslighting, and emotional abuse began.

In the past, he had violent blowups when things didn’t go his way, but the violence was never directed at me. I remember, after college, when he received a lower LSAT score than he thought he deserved, he blew up into a fit of rage: throwing objects into the floor and walls. Crying and shouting at no one in particular. It shook me, but I didn’t feel as if I was in any real danger. Later, during COVID, that would change. There were many red flags like this throughout our ten-year relationship, but I didn’t see them, or I ignored them, or I explained them away. Now, looking back, I see them everywhere. My personal experience was invalidated and disregarded, constantly. I was pressured into being intimate, convinced it was my responsibility to make sure he was satisfied, and there was little to no consideration of my pleasure.

At the same time, a professional relationship with an older mentor figure became increasingly toxic. Though we only met in person a few times that year, we spoke on the phone often. We would argue about facts. She would use her status and degrees to demean me and diminish my skills, intelligence, and creativity. She would threaten my future, and I began to believe that she held the keys to my professional success. Many of our calls ended with me on the floor, crying and pleading for the yelling to stop. I didn’t understand why so many of our conversations went in this direction.

Image Description: A digital collage of the Virgin de Guadalupe in front of a brightly colored gradient background made from the colors of the Mexican flag: red, green, and yellow. At the bottom of the collage is the word “sensitive”, in large bright pink letters. The maternal figure in the image is dressed in a red-orange dress, and a green robe with gold stars on it. She holds a pink rose that is glowing. Around her is a burst of gold glitter, and a she stands atop a bed of roses. She has green teardrop-shaped emeralds around her head in the shape of a crown. At her feet is a golden statue of a cherub angel with its arms crossed. The angel rests its chin on its forearms.

To make things worse, my boyfriend grew increasingly jealous of my time spent on work, furthering my career, and speaking with friends in the online disability community. So much so, that by mid-2020 I was allowed to bring those things up in conversation. In the evenings, if I tried to share something about work, or talk about a conversation I had with a friend that day, he would get angry with me. I began to feel, more and more, that there wasn’t – and maybe hadn’t ever been – room for my “full self” in this relationship. The only version of me that was deemed “acceptable” was the version of me that tended to his physical and emotional needs above all else.

And then, Abilitee split apart. My former business partner, who funded the operation, went their own way. They started a new brand, and I kept the Abilitee name along with all of my research, designs, and ideas. But I was in a horrible place, mentally, emotionally, relationally, and physically. I had stopped taking care of myself, in nearly every way. I was doing what I could to feel safe from further abuse. I was self-medicating to cope. I was surviving, nothing more.

And things just kept getting worse. My boyfriend and I rented our first apartment together in a sketchy neighborhood of East Los Angeles. We didn’t have a yard, and I couldn’t walk my dog around the block at night without worrying for my safety. Everything in LA was still closed down. We both worked from home. He would be on the phone all day, talking to clients, his voice echoing through the apartment for hours on end. The neighborhood was loud, too: there was constant commotion in the apartment complex, police and fire truck sirens blaring every other hour. At least once a week, helicopters boomed through the night sky, circling the area with spotlights and looking for suspects on the run. One night, around 2am, I heard gunshots nearby. For the next two hours, I watched as our street lit up with police lights, a crime scene was taped off, neighbors would be interviewed, and an ambulance came and left. I couldn’t escape the noise. It was sensory hell.

We started fighting more. He started screaming louder. Stalking me around the apartment, looming over me while tearing me down. I grew more and more confused and disoriented in my relationship, which affected my grasp on reality and the outside world. I had many meltdowns that year. My emotions were everywhere. I was so overwhelmed. I stopped achieving any level of productivity in my work, and we missed several of target re-launch dates for Abilitee. My life felt completely out of control. I felt worthless – like I was letting everyone down, including myself. And then, towards the end of 2021, right as our apartment lease was about to expire, I got dumped, and it sent me reeling.

Confused, terrified, hopeless, helpless, traumatized, I went home to Texas. With no one left in Los Angeles, it just made sense. My dad helped me pack up my life in California. At 30 years old, I moved back into my childhood bedroom. There, for the first time, I was forced to confront everything that had been my world and my life for the past 30 years. Because, clearly, it wasn’t working. Everything had to change. And for me, the first step forward in this process of healing, was figuring out how the fuck I ended up here.

Butterflies & Goo

As children, we learn that caterpillars become butterflies through a transformative process known as metamorphosis. When it’s ready, a caterpillar finds a nice little spot to park itself on a twig, where it builds a protective chrysalis around its entire body. Days to weeks later, the chrysalis breaks open, and a fully-formed butterfly emerges. But only relatively recently did scientists discover what happens in-between. As a child, I believed that – over time – the caterpillar would sprout the legs, wings, antennae, and other morphological structures we observe in fully-formed butterflies. Many people thought this. But that’s not what happens at all. Before a caterpillar becomes a butterfly, its body releases enzymes into the enclosed chrysalis, which effectively digests (i.e. disintegrates) itself until the insect becomes an unrecognizable glob of goo – something slimy and gross that resembles neither a caterpillar nor a butterfly. And yet somehow, as the process continues, the molecules that make up this goo figure out how to reassemble themselves in an entirely new, incredibly beautiful way. A butterfly forms, like a phoenix rising from the ashes. It seems magical, but it’s simply part of their programming. And the most wonderful thing – I believe – is that we are like this, too.

Just like caterpillars, I believe that children possess an innate wisdom about who they are and what they can become. And with the right nutrients, environment, and support, a beautiful future can be made possible. But unfortunately, for so many of us – especially for those of us who are queer, disabled, neurodivergent, non-white, or from any other marginalized community – we don’t always get that support. We’re taught to suppress and fight that inner wisdom and our understanding of our own wholeness by a society that continually, violently chooses to do the same.

Growing up, I always felt different. And others’ reactions to my tiny bursts of authentic self-expression confirmed this for me, over and over and over again. I would ask questions for clarification, when I really wanted to understand something; I would share unique takes on things, perspectives others hadn’t considered; I would wear something that felt affirming of my identity; I would come at a problem or challenge from a very different direction. And the world told me “no,” over and over. “It doesn’t work that way. Why are you making things more complicated than they need to be? Why are you asking so many questions when everyone else seems satisfied?”

So, as I got older, I learned to bypass my own internal compass. Clearly, my needs were wrong. Clearly, I didn’t know what was best for me. (/s) So I looked everywhere but inwards for validation and acceptance. Instead of trusting my own instincts, I spent an incredible amount of energy observing and analyzing everyone else. I absorbed everything everyone around me was doing – what other kids talked about, what they wore, what made them laugh, what movies they watched on weekends, what their parents put in their lunchboxes. And I tried my best to be like them. There was safety in “sameness.”

Masking became an armor for me. Every morning, from grade school through college, I put on my armor before leaving the house – carefully, intentionally, and painstakingly. I straightened my long wavy hair to look “less Mexican.” I learned to camouflage my quirks – to hide any part of me that stood out “too much” in my wealthy white conservative neighborhood.

I fell in love with fashion the moment I was able to dress myself. To this day, one of my favorite activities is playing dress-up. Bright colors, soft fabrics, and beautiful shapes provide such satisfying sensory stimulation. Growing up with undiagnosed ADHD (a developmental disability) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (a chronic mental illness) meant I was constantly trying to keep up with those around me, without the proper support. I often found it difficult to express myself with words. Even when I knew what I wanted to say, social anxiety got in the way. Fashion became a tool I relied on to communicate with the world — it was a language I became proficient in very early on.

I grew up with specific options for how and who to be. How and whom to love. Which careers were “worthy” of my intelligence and economic class. Boxes offered to me by distracted adults. By celebrity role models, by friends’ parents, and by the opposite sex.

I learned it was my job to satisfy men. To make men comfortable, to make them look good – but never overshadow or outshine them. It was my job to keep others’ fragile egos intact (only it really wasn’t, but how was I supposed to know?). I learned to be pretty, but silent. To be accommodating. To manage others’ emotions — especially men’s.

I thought I needed to land the most lucrative job to be a valuable human. I thought I needed to be popular. I needed to be not only accepted, but praised by those around me, as a means of determining my own worth. But that just led me to stifle my individuality. My personhood. I watered myself down to meet others’ expectations of who I was and who I could be. I let others determine who I was allowed to be.

And for those of us who are lucky – I do feel I am lucky – maybe the goo is a necessary, unavoidable, uncomfortable stage, if we are to continue transforming into who we’ve really always been. The goo is part of the transformation. For me, everything had to fall apart, in such a catastrophic way that I became so unrecognizable to myself, that I would eventually be forced to stop, take inventory of all of my pieces, and start rebuilding my life anew.

In the world through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself. – Frantz Fanon

I like the idea that I’ve been incubating, germinating, thinking, considering, making connections, identifying patterns, and integrating all of that learning into developing a better understanding of myself and how I might safely and authentically live in this world.

Out of necessity and curiosity, and with guidance from queer neurodivergent friends, I began to venture down many rabbit holes. I devoured everything I could learn about abuse, autism, and compulsive heterosexuality. Piece by piece, I interrogated everything I thought I knew about myself and the world around me. I began deprogramming the “good girl” mentality, and no longer placing others’ opinions about my life above my own.

The three adaptive products are shown in front of a photo of the Futurekind studio. The studio is a bright space with white walls and light wood floors. The studio is decorated with vintage rattan furniture and leafy plants in simple gold-painted plant pots. Bright pink blankets are laid across the furniture. A large disco ball sits on a table.

In many ways, I feel I have come full circle by meeting and embracing my childhood self again – who I was before all of this conditioning and societal pressure crusted over me like a cocoon.

Most importantly, I believe, I made the decision to simply begin this process of evolution. To me, this resurrection wasn’t about re-emerging as someone new, all at once, with all of my trauma healed and my future life figured out. I now understand that the process of metamorphosis isn’t about a sudden, fantastical transformation. It’s an entire lengthy process of un-becoming, of sitting in all of that goo, and then making the decision to trust my innate programming, as uncomfortable as that may feel, over and over again. Lasting transformation, in this way, is necessarily slow and deliberate.

It requires questioning everything: tearing down our internal systems and constructs, breaking our lives into a million little pieces, and then creatively, fearfully, forcefully, and optimistically piecing things back together in a way that is more in line with our inner selves and what we want to see in the world. We simply must begin. Again and again, as needed. And if we’re lucky enough to have the resources and support, and we choose to put in the work, we can build a better life for ourselves each time. And if we’re loud about it, I believe – I hope – we can build a better world for others, too.

In a similar vein, I believe the purpose of a studio is to serve a safe, nourishing home for those who wish to continue evolving and improving their lives and the world around them.

Through Futurekind Studio, I’m building a creative home for myself. But hoping to build a creative home for others as well. Art heals. Community heals. Design has the power to shape people’s lives, for better or worse. I’m happiest when I’m in my studio. Unstructured creative time. Or when I’m talking with others – ideating about what could be.

Even decorating the studio has become a process about taking ownership over and responsibility for loving and cherishing my own special interests, while building potential for others to come in and do the same.

Finding My Wings (Again)

Image Description: A cut-out photo of Elena taking a selfie is in the center of the image. She is a medium-light-skinned Latinx person with dark brown hair braided up in a crown. She is kneeling on the ground and holding up her phone in front of her face. She wears a long sleeve body-con dress printed with rainbow-colored dollar bills all over it. She wears white, pointed-toe booties. In front of her legs is a bright blue iridescent butterfly with green teardrop shaped emeralds all over its wings. Behind Elena is a hot pink background. At the top of the image is dripping goo made of green sequins. On the left side of the image is a purple, liquid-like hand drawn logo for Futurekind Studio. The logo is glowing bright yellow.

Queer fashion is healing. For me, over the past year, fashion has played an incredibly significant role in my “becoming,” and at the same time, I often feel that I have spent much of this time revisiting who I was and what I loved to wear as a child.

Growing up in Austin, and away from my Mexican relatives, I tended to identify more with my white, “gringa” family and heritage. But interestingly enough, the times I spent immersed in Mexican culture were always more salient, more memorable. Only now, as I’ve begun to explore myself, my tastes, and my passions, have I come to understand how very deeply Mexican I am. As uncomfortable as it is to say, I always thought of my caucasian-American heritage as “boring,” and my Mexican heritage as exciting: warm, welcoming, vividly colorful, and something that set me apart from my peers. Different in a good way. Something I was proud of, even as a child. I saw this part of my history as a sign of strength and perseverance against all odds. From this side of my family, I witnessed a shared emphasis on the experience and exploration of being alive: feeling, loving, cooking, eating, dancing, joking, kissing, singing, painting, creating.

In recent years, I had forgotten these things were a part of me. I deprived myself of all these things — perhaps as a form of self-punishment, for failing to meet the norms and expectations of the very non-Mexican community I lived in for most of my life. I had learned in so many ways, and from so many outside sources, that the meaning, purpose, and value of my life was my ability to achieve and produce. Not to feel, enjoy, love, or create.

I have such fond memories of visiting my Abuelita where she lived near the border. My siblings and I would stay with her, usually for a week at a time, during summer break. We’d cross the border to Matamoros, Mexico and spend hours with her at the small tuxedo and formal wear shop that she owned and ran. She was a skilled seamstress, and as I got older, I learned she was a talented artist as well. I believe I have her to thank for these wonderful gifts that I seem to have inherited. And the more I remember my visits to Mexico, and my time spent in her shop, the more I recognize how much of her life and culture I absorbed.

Now, as I am rediscovering my taste for vibrant, warm, saturated colors – compared to the cool blacks and grays and neutrals I wore for much of college – I am realizing how fondly I remember those times spent in the streets and markets of Matamoros, just wandering around as child and taking everything in: excited by the bright colors of traditional Mexican art and the textures and craftsmanship of the woven textiles that were everywhere. And I have certainly noticed, over the past year or so, how wonderful, and light, and optimistic, and free I feel when I’m wrapped in clothing that gives me that same sense of comfort and awe and excitement that I felt as a child exploring the street markets of Mexico.

I think I understood very early on how color, shape, and design can change the way we interact with the world. When used thoughtfully, it can excite and inspire us – and now is such a ripe moment for using this to our advantage. Fashion, I believe, is an incredibly effective medium for changing cultural attitudes and encouraging social and political change.

Through Abilitee and Futurekind Studio, I want to help make the disability revolution irresistible: to make it visible, powerful, effective, authentic, relatable — to use fashion to push for change. If I can help someone understand the importance of having clothing that fits different bodies and different modes of self-expression, then maybe that opens up the conversation to start thinking more comprehensively about disability inclusion and accessibility in other areas. I want to be part of a future where fashion is used to encourage and promote inclusivity, rather than exclusivity, as most of the industry does now. To me, such a future sounds much more interesting, challenging, and rich, with so much more room for all kinds of people to exist freely and joyfully and colorfully. I think it’s time for us to evolve. Will you join me in making the decision to begin? Not just now, but over, and over, and over again?

about the creator

Elena is standing holding her dog Archie in Futurekind Studios which is decorated with disco balls and plants. She is a medium-light-skinned Latinx person with dark brown hair braided up in a crown. They have on bright pink lipstick, a purple top with blue, yellow, green and black graphic sleeves and large pink earrings.

Marta “Elena” Cortez-Neavel (she/her/they/them) is an queer, neurodivergent, Mexican-American artist, designer, and activist based in Austin, Texas. Her work focuses primarily on disability, gender, and size inclusion in fashion and the creative industries. Elena is the creative director and lead designer of Abilitee Adaptive Wear, and the founder of Futurekind Studio, an inclusive creative home for other marginalized artists.